By Lina Nagell

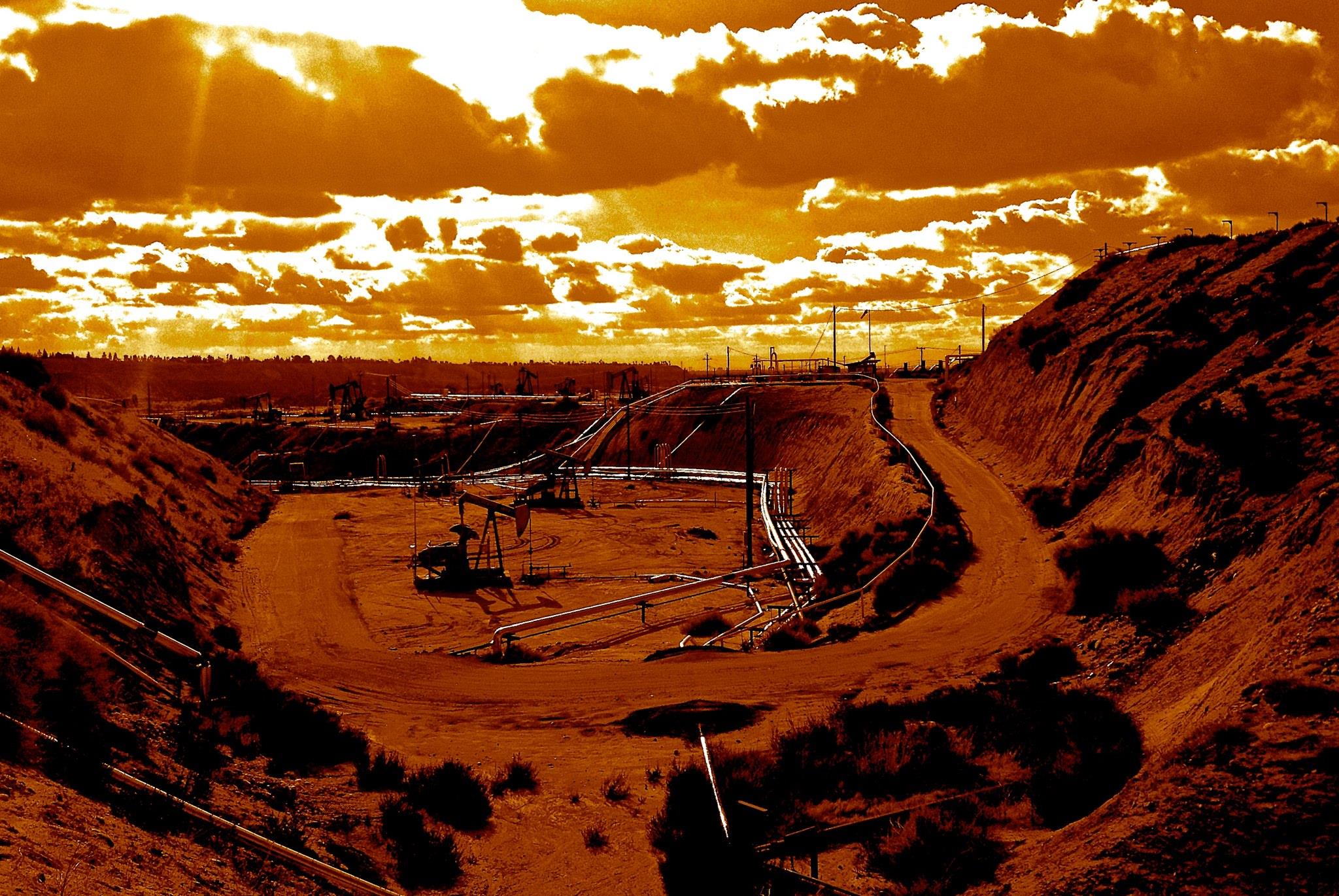

Photo: Jerry D. Mathes II

Saudi Arabia has functioned as a global swing producer in the oil market since the 1970s, before abandoning its role in 2014. Amongst changing market conditions, some observers still latch on to the idea of a global swing producer. While some believe in the resurrection of the old system, either with a new (read non-OPEC) consortium of producers as a swing producer, some observers point to the U.S. as a potential swing producer. Others believe the world is heading towards a new reality in the oil market, where new technology will make the market more adjustable to changes in demand and supply, changing the power of the stacks of market share held by major producing nations. I will take on the former view, and line up some of the major issues related to a future global swing producer(s).

First things first

What is a swing producer? There are different and contesting definitions as to what a swing producer is. Investopedia states is to be: “one (producer) who quickly, easily and, most importantly, cheaply increases and decreases oil production to meet shifting global demand patterns.”

As mentioned by John D. Morecroft in his article Modelling the oil producers, a swing producer operates in two modes: (1) normal swing mode or (2) punitive mode. While the actions of the swing producer in a normal swing mode consists of setting a production rate that is “equal to the swing quota, unless the oil price deviates from the intended market price”, the actions of a swing producer in punitive mode consists of re-establishing its position in the market, as a result of lost market share, by increasing production and as a result “punish” other producers in the market. At the basis of these functions of a swing producer, is the assumption that the swing producer can indeed work as one production-regulating entity.

From history we know the troubles within OPEC, specifically related to the incentives of free riding, to work as one swing producer. Saudi Arabia has in practise been the swing producer in the oil market since the 1970s. By stepping into punitive mode in 2014, the Saudis have up their role as regulator, leaving the market unmanaged, according to Morecroft.

But is this really the case? Is what determines a swing producer the realistic ability to influence the price, or the actual actions to do so? This would be determined by the ability of Saudi Arabia to reclaim its role as a swing producer.

Saudi Arabia: getting back into the swing

With market conditions changing, being unpredictable, and with the rise of new oil exporters on the scene, there is definitely an argument to be made for a potential difficulty in OPEC, with Saudi Arabia at its hem, regaining its status as swing producer. There is, however, no denying the facts. If Saudi Arabia wished to influence the price, being the largest exporter of petroleum in the world, there should be nothing standing in the kingdom’s way, in the short run – resulting in a loss of market share, and possibly credibility in the market, by Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia is caught in a rough spot. While production costs of oil are some of the lowest in the world, the regime’s non-democratic character and social contract makes the country reliant on a high oil price. This need brings many observers to doubt the longevity of the production increases started in 2014. Recent developments, such as the meeting in Doha between Russia and Saudi Arabia, and the importance put on Iran’s participation in potential production costs, can be a sign that Saudi Arabia is not interested in going back to a leading role as a swing producer, but more interested in sharing the responsibility of price controls with other major producers. It is important to note that this is an interest based in strategy of retaining market share, not an inability to influence oil prices by production regulation.

U.S. as a swing producer

While OPEC has historically had access to spare capacity as a tool of easily responding to changes in the market (albeit with some exceptions), the U.S. situation is vastly different. It is true that the U.S. shale revolution has brought with it technology which decreases the time lags usually associated with the oil market, but U.S. drillers’ ability to increase flexibility and decrease this adjustment period is imperative to any swing producing role the U.S. might ever take on.

The main argument against the U.S. operating as a global swing producer is the inability of the U.S. producers to act as a unified production-regulator of oil production. There is in fact no evidence, which might suggest that the U.S. oil industry is able to work in a coordinated manner, which is the key to actually functioning as a global swing producer. Even if U.S. drillers were to overcome the obstacle of response times to market changes, the underlying free rider problem amongst many small players in the U.S. market, would have to be overcome for the U.S. to function as a swing producer.