by Henrik Vorloeper

In February 2016, the European Union Commission proposed a new directive on gas contracts, in which the Commission further extends its control over EU member relations with non-EU suppliers. Even if the new directive might take up to two years, which is according to Platts a normal time exposure to adopt new regulations in the EU and will thus not have an immediate impact on the current contractual situation, the draw is yet another step of the EU to increase its energy security in a situation of high reliance on imports.

In the past several of years, the EU has taken multiple initiatives to reduce the reliance on foreign markets, mostly by efforts to integrate and liberalize the market and to create diversification on the supply side. Most significant was the implementation of the “Third Energy Package” of 2009 and the decision of 2015 to create the “Energy Union”.

Most of the EU gas demand is satisfied by Russian gas and the main supplier Gazprom. Gazprom’s dominant position in Europe is a thorn in the flesh of the Commission. The EU wants to reduce Gazprom’s influence in Europe and any new adopted regulation is certainly perceived in Russia as another attempt to create a barrier to Gazprom’s export strategy.

Indeed, the new directive proposes several novelties, amongst which one appears troublesome for Gazprom. With the implementation of the new directive, any EU gas company that signs a supply contract with duration of more than one year with a non-EU supplier has to submit the contract conditions for review to the national authorities and the EU prior conclusion. The Commission will review the conditions and the parties are expected not to sign until the Commission has given its feedback. Companies retain the right to sign any contract, but are expected to take the Commission’s recommendation into consideration. Whether or not the companies and member states will follow their advice, the EU sends a political message that it does not hesitate to expand its influence over the gas sector and that it demonstrates mistrust over Gazprom’s opportunity to utilize its dominance on the market in many European countries. Currently, the Commission investigates possible violations of the antitrust law in the EU by Gazprom.

Also, it is no secret that the practice of long-term gas supply contracts is a caveat to the EU’s liberalization policy. This, however, reveals the problem that regulatory control influences the evolution of energy markets. While the EU encourages the liberalization of its energy sector and attempts to restrict Gazprom supply monopoly, it appears to forget the certain aspect that the hydrocarbon sector requires above-average investments into sunken costs, such as exploration, the construction of pipelines or LNG facilities. Gazprom so far has recovered its cost with guarantees of demand via the implementation of long-term contracts.

In theory, less long-term contracts and the creation of spot markets will lessen Gazprom’s security of supply. In reality, the EU reduces Gazprom’s ability to implement unfair gas prices over its customers who are unilateral dependent on Russian gas. In general, the EU sends a political message to Moscow, since it does not have the authority to liberalize the Russian energy sector and to cease Gazprom’s export monopoly. For more than a decade, the EU has gradually reduced its vulnerability position of being dependent on Russian gas, while admitting that Russia is still the most economic viable option.

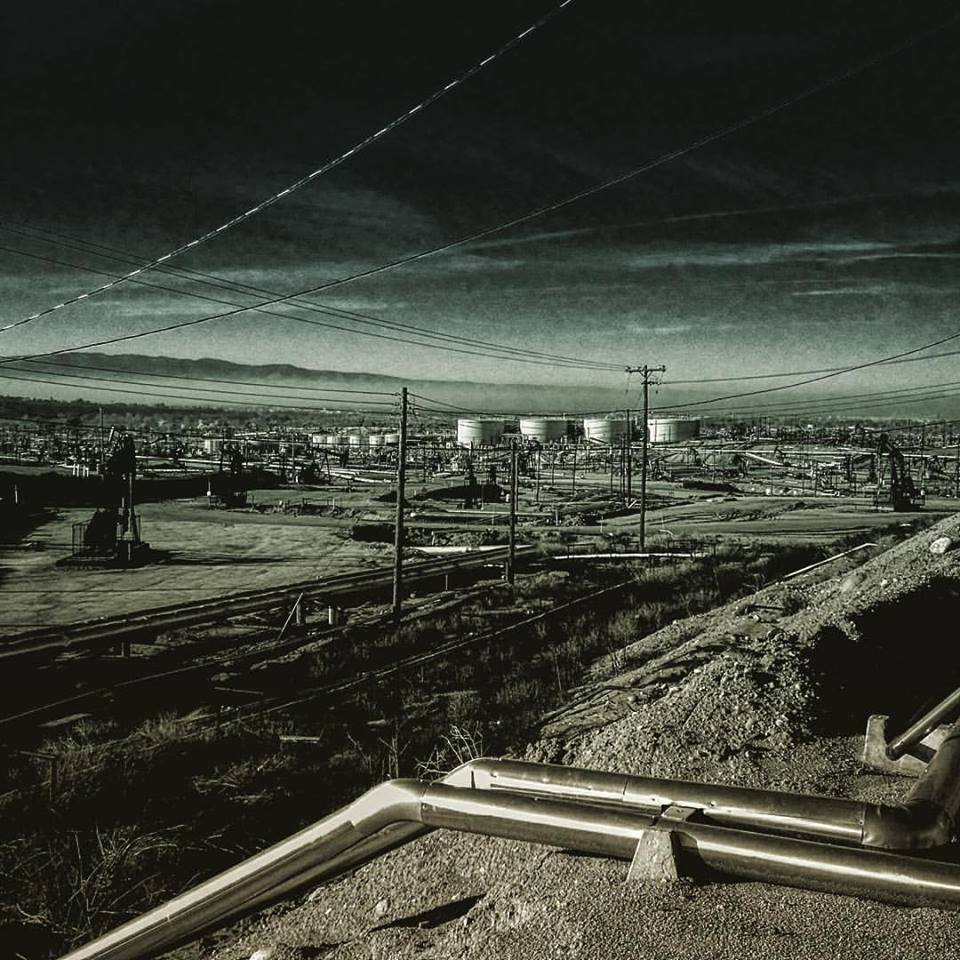

(photo by Jerry D. Mathes II)