Rethinking the Role of Gasification and Electrification in ASEAN Energy Security Initiatives

Cory Cox

Abstract:

This article discusses the complexities of trying to apply foreign gas hub models to developing countries and regions. The challenges of implementing a regional gas strategy amongst the ASEAN members regarding the Trans ASEAN Gas Pipeline are reviewed and alternative energy cooperation models are presented. Specifically, we address the opportunities for cross-border electrification programs through a variety of mechanisms including the development of more renewable sources. We argue that efforts to create a regional natural gas infrastructure in ASEAN are shortsighted and that regional coordination should be forward looking such as providing an infrastructure that can support a shift in primary fuel consumption toward RES.

Key words: Natural gas, electrification, energy poverty, ASEAN, salt domes, underground natural gas storage; gas hubs; LNG; Renewable energy: Trans ASEAN Gas Pipeline

As evidenced in natural gas markets in the United States and Europe, attempts to apply the experiences of one market to develop target models for another often suffer from oversimplification. Historical path dependencies and other geographical features are often absent from the models that tend to focus on market reform as simply a matter of regulatory and legal reform. For example, a more complete understanding of the historical development of the US natural gas market reveals legislation, which forced gas suppliers and consumers to break existing contracts – in direct contrast to an unyielding legal tradition of inviolable contracts or pacta sunt servanda – which unleashed the liberalizing effects of deregulation by unbundling transport from gas ownership. Equally, target models often attempt to establish trading hubs with little consideration for storage services and the geological realities that dictate that the presence of salt formations favor some locations more so than others. The Trans-ASEAN Gas Pipeline (TAGP) project appears to suffer from the same oversimplifications and a lack of consideration for historical contingencies of regional cooperation in ASEAN.

Gasification of the region is dubious given the wide variance in electrification and electricity’s more important role in alleviating energy poverty. This is especially true in a region where household heating is non-existent. Today, electrification ranges from a low of only 26% in North Korea to full access in Singapore (see Figure 1).

Gasification in ASEAN is misguided as it may lead to a redirecting of investment into pipeline infrastructure that generally only supports industrial consumers at the expense of electrification infrastructure that can generally benefit all. However, this does not make the TAGP project misguided. The following chapters outline recommendations for further development of the Trans-ASEAN project in order to improve ASEAN regional security, both in terms of energy security as well as security more generally.

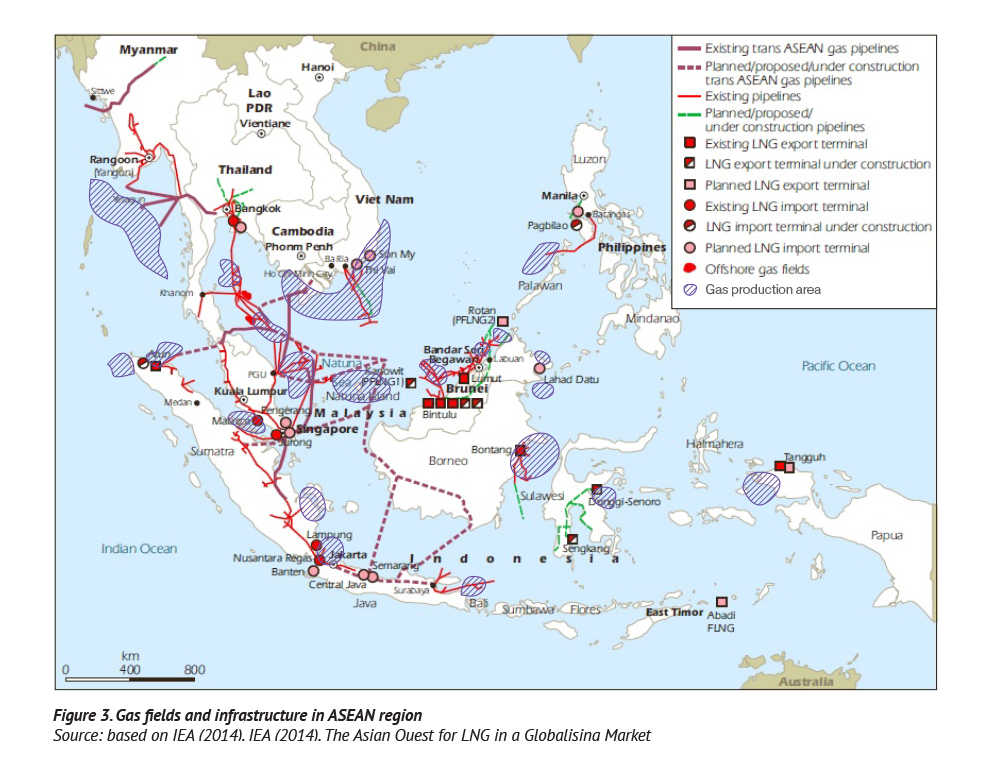

Narrowly Distributed Benefits

Gasification as an end goal is likely to result in a less favorable market than electrification, namely resulting in market distortions. Therefore, end consumers will be limited to power generators who will be bearing the costs of a transportation network that does not enhance their ability to reach end consumers of electricity. This subsidy for the construction of the TAGP will be reflected in the price of gas, regardless of unbundling. Furthermore, proven reserves (see Figures 2 and 3) are evenly distributed near consumers of gas – unlike Russian gas supplies and European consumers – suggesting regional development should enhance opportunities to distribute electricity. Counter arguments suggest that gas market development will be hampered by a lack of interconnectors. However, a well-developed, liberalized regional electric market can develop by way of high-voltage direct current (HVDC) interconnectors and will force gas market pricing to be competitive in the presence of regional LNG and electricity linkages between the localized gas markets. This will more effectively allow for both regional energy security and alleviation of energy poverty in states such as Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia.

Hubs: Singapore versus Northern Thailand

Often, justifications for a pipeline interconnecting ASEAN cite that infrastructure is needed for a proper LNG market. This is unfounded. Gasification terminals are currently built or in the process near sources of gas throughout the region.

The existence of interconnectors only adds an additional cost burden by having redundant networks for gas supplies that ultimately are liquefied (pipeline and LNG train). An LNG hub may develop out of Singapore, but there is no reason to predict emergence in Singapore over any other location without further examining the analogues for pipeline hubs to LNG hubs, namely analogues for merchant storage and transport unbundling.

What is more fitting to predict is the emergence of a pipeline-based gas-trading hub in Northern Thailand and Laos. Trading hubs are characterized by the presence of many suppliers and consumers, as well as merchant services that support trade: online trade exchanges and merchant storage. The most important requirement is the latter, as it determines the geographical location of hubs. The former precondition is a matter of regulatory and legal frameworks, which can theoretically be developed in any location (with varying degrees of success). But the presence of affordable and effective merchant storage cannot.

Salt formation storage is universally seen as the most cost effective and technically feasible storage. This suggests that the Maha Sarakham Salt Formation in Northern Thailand/Laos will provide the ideal nexus of adequate merchant storage in salt formations at the border of the world’s most viable consumers of natural gas: Chinese electricity producers (see Figure 5).

Evidence of co-location of gas trading hubs with salt formation storage is a well researched, yet rarely discussed, correlation. This is clear in Europe as shown in Figures 6 and 7 as well as the presence of salt formation storage for gas at the Henry Hub in the US (see Figure 8).

ASEAN and Mega Projects

Benjamin Sovacool, one of the most prolific scholars on the Trans-ASEAN projects, argues that regional mega projects are historically quite difficult to see implemented, and specifically TAGP is even more challenging given the peculiarities of stakeholder interests in the ASEAN region. Although Sovacool tends to see the project as detrimental to the environment, I would argue that a less ambitious and less regionally coordinated set of projects would create a net reduction in CO2 pollution. For the purposes of “shutting in” dirty and unsustainable coal in China, joint projects with Chinese investment into pipelines with a destination in the Laotian-Chinese border will result in a market-based trading hub for Chinese buyers with several states in ASEAN. But a fully integrated regional network comparable to NBP in the UK or the EU network currently being shaped is misguided.

Bilateral Projects with China: Navigating the South China Sea Disputes

Finally, I contend that ASEAN should focus on the development of HVDC interconnectors only while encouraging member states to pursue joint ventures with China to develop gas pipelines to bring gas to a Thai-Laos-Chinese pipeline gas hub. China and the region will benefit from infrastructure development that is forward looking. Development of a transportation network that can support gas as well as renewable primary energy sources will ensure the network does not retard adoption of RES as investments in gas infrastructure make adoption uneconomical.

Yet, energy security in the Asian security complex is increased by sustainable development in China matched with a de-escalation of regional border and maritime disputes. As proposed by Stewart Taggart of Grenatec, joint ventures that provide China with long-term contracted gas supplies at market-indexed prices from South China Sea sources could achieve significant improvements in regional energy security.

Although the project proposed by Taggart is a mega project, a more limited-scale approach could achieve similar results. Instead of a coordinated effort to resolve all island disputes and build an extensive regional network at once, projects could be firstly developed with Vietnam and Laos to clear the way for future land-based pipelines to a new hub at borders of Laos and China (see Figure 9). Likely, Malaysian and Philippian disputes will be more manageable than those involving Taiwan. Yet there is no reason to believe that precedent cannot establish a regional energy security approach that tips the scales toward win-win (as opposed to zero-sum) approaches to regional energy security.

International Energy Agency: Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2015

The outlook for ASEAN electric power generation, based on the most recent IEA report, is marked by a dramatic decrease in the use of natural gas (44% to 26%) as coal-fired electric generation takes the clear lead, moving from 32% to 50%. As the IEA suggests, “oil and gas supply outlook is constrained by a mature resource base with the most prolific fields starting to decline”. These constraints seem to underscore our contention that a Trans-ASEAN gas pipeline network is the more reactionary regional approach to securing rapidly growing demand as opposed to a creating a vision for future sustainability.

However, this dangerous trend in regards to CO2 emissions underscores a need to not only focus regional integration efforts on HVDC interconnection, but also to ensure that hydropower and other renewables drive power generation in Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia, which are projected net-exporters of electricity based on existing and planned projects. Figure 10 outlines the various findings of the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia’s (ERIA) report on the potential implications and benefits of enhanced power grid interconnections. The potential benefits outlined, such as a reduced need for additional gas-fired or coal-fired power plants, would be negated if the power imported into states such as Thailand were generated using fossil fuels – simply shifting CO2 impact from one ASEAN state to another.

THE WAY FORWARD

Development of regional markets is not a one-size-fits all set of policies and pipeline or power-line projects. Liberalized markets depend on not only networks for transport of energy to and from hubs, but also storage of energy at such hubs. Further, energy poverty is detrimental to full realization of a regional market, leaving vast numbers of untapped potential consumers outside the market. This may distort markets toward industrial consumer needs and the colocation of power generation in industrial centers. Should taxpayers bear any burden of gasification pipeline mega-projects, they will effectively subsidize these industries. Moreover, these public investments will be diverted from projects that could alleviate energy poverty more generally, and not just for industrial areas. Lastly, mega projects have historically been difficult to implement.

Instead, less ambitious projects directing pipeline construction towards China, whose demand for gas is growing rapaciously, would seem a more logical solution. These projects also have the benefit of being limited partnerships between individual ASEAN states and China, making them less ambitious and less challenging to implement. Further, partnerships between ASEAN member states and China could provide opportunities to reframe South China Sea disputes to provide benefits to all through development of projects that effectively settle outstanding disputes via creative sharing agreements.

Looking forward, the most recent IEA outlook suggests that coal is likely to outpace oil and gas in electric power generation, as mature resources are increasingly less economically viable and in decline. This only strengthens the arguments we have laid out for a more targeted approach to regional energy security through cooperation. In conclusion, regional interconnectors to export electric power via HDVC with an increased reliance on hydropower exports can help to reduce CO2 emissions and reliance on fossil fuels (natural gas and coal) for electric generation. The general contention is that energy security will be enhanced when both energy poverty and more traditional security issues are incorporated into a holistic approach to regional security.

Cory M. Cox

Graduate of the ENERPO certificate program at the European University at St. Petersburg (spring semester 2015). He received his first MA degree in Political Science as well as a second MS degree in Justice Administration from the University of Louisville. Cory is currently a PhD student at the Center for Network Science at the Central European University in Budapest, Hungary. Cory’s areas of scientific interests include energy poverty in South and Southeast Asia as well as the social organization of energy black markets in the Middle East.

Address for correspondence: cox_cory@phd.ceu.edu