By Michael Roh

Abstract

Russia, the country with the largest natural gas reserves in the world, is notably one of the largest greenhouse gas emitters. Therefore, its participation is crucial to the legitimacy of any international climate change agreement. At the 21st meeting of the Conference of the Parties in Paris, referred to as COP21, Russian President Vladimir Putin delivered the message that climate change is a global threat and Russia is ready to act. Western media lambasted the leader and criticized his intentions. This paper seeks to identify where Russia stands on climate change, whether its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution is sufficiently ambitious, and why taking steps to curb climate change is in the country’s interests. The potential to introduce renewable energy and the barriers to initiating renewable projects are also discussed.

Key words: climate change; COP21; Paris Agreement

- Introduction

At the 21st Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP21), no one expected Vladimir Putin, in his address to the U.N. Member States, to declare that governments must act against global warming. Putin even took the opportunity to boast of Russia’s significant contributions already made to combatting climate change.

Could the West’s go-to villain actually care about climate change? Is Putin correct in claiming Russia has already made efforts to reduce emissions? Given that the consequences of climate change affect countries disproportionately, could it actually be in Russia’s interest to combat global warming? Should the West be so quick to lambast a country willing to cooperate, when that country is responsible for such a significant share of global greenhouse gas emissions, a country that depends on its fossil fuel exports to sustain its economy?

These are all questions this paper will seek to answer, identifying individual points in Putin’s speech at COP21 to uncover Russia’s true intentions when it comes to climate change.

- What is the Paris Agreement?

Building on the efforts of the UNFCCC[1] and the negotiated commitments in the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement was adopted on December 12, 2015. While the Kyoto Protocol sought to rally countries to reduce emissions in an effort to keep global temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the Paris Agreement ambitiously strives to stop temperatures reaching above 1.5 degrees Celsius.[2] Scientists agree that allowing temperatures to exceed this threshold will have devastating and far-reaching environmental consequences.[3] For the Paris Agreement to come into force, 55 countries (accounting for at least 55 percent of GHG[4] emissions) must ratify the treaty.[5] Countries were advised to submit an INDC[6] before the conference, and Russia was one country that submitted its INDC months before the conference, committing to cutting its greenhouse gas emissions by 25 to 30 percent of their 1990 levels by 2030.[7]

- Is Putin taking too much credit?

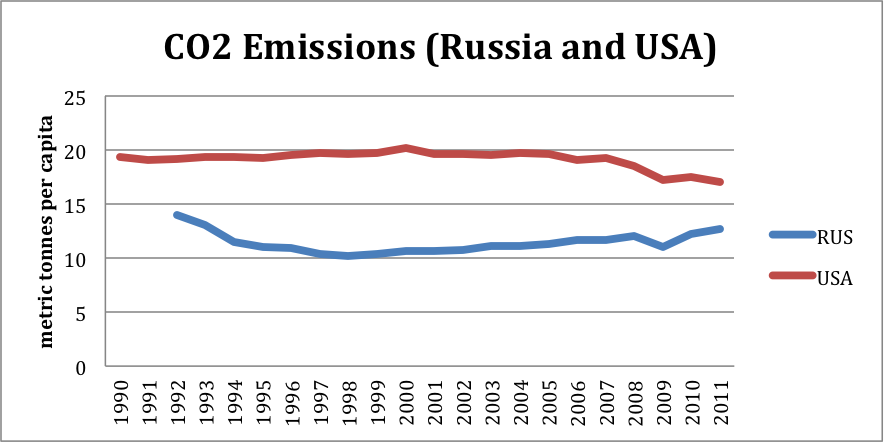

The Kyoto Protocol required countries to keep emissions of six greenhouse gases below levels of the base year (1990), which Russia committed to for the 2008-2012 period.[8] For Russia, this has been a rather easy task, considering the early 1990s was a time when the Soviet Union’s heavily energy-intensive industrial economy collapsed. Figure 1 displays the sharp decrease in emissions for Russia in the early 1990s. Therefore, it’s hard to ignore that Putin is taking too much credit for achieving a less-than-ambitious target. The graph also displays, however, emissions from the U.S., where emissions only started to decrease in recent years, due to the shale revolution, which one could argue is also convenient, given that natural gas burns much cleaner than oil.

In Paris, Putin took the opportunity when addressing fellow U.N. Member States at COP21, to boast that Russia has already made a significant contribution in the fight against climate change while still growing economically. Regarding emissions, Putin boasted of how Russia has reduced its energy consumption by 33 percent from 2000-2012, while projecting a further 13 percent reduction between 2015 and 2020. Additionally, 46 million tonnes of CO2 were not released into the atmosphere thanks to Russia’s industrial modernization and clean technology. Putin proudly claimed these achievements were made while doubling Russia’s GDP. It’s true that Putin is taking undue credit, but that same moral standard should be placed upon other developed countries, including the U.S.

Figure 1 Source: World Bank

Figure 1 Source: World Bank

Putin also spoke on the importance of forests, which act as carbon sinks. A carbon sink is “anything that absorbs more carbon than it releases.”[1] Indeed, vast areas of Russia are forests, with estimates stating the country contains 640 million trees.[2] This allows Russia to negate a generous share of its emissions through the effects of its forests. In fact, after accounting for forestry, Russia’s INDC proposal to reduce GHG emissions by 25 to 30 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, is actually only a reduction of 6 to 11 percent below the 1990 level.[3]

- Why climate change action is in Russia’s interests

Despite claims by Western media that Putin is only pretending to care about climate change because of a hidden agenda, namely, diverting attention away from the situations in Syria and Ukraine, some believe Russia is looking to increase its soft power by showing the world it is a cooperative partner. Russia, once a country that received aid, seeks to gain the prestige that comes with being a donor country.

The International Business Times wrote, “Russia has a reputation as one of the most difficult states involved in international climate negotiations – and don’t expect things to change at the latest UN conference in Paris. After all, this is a country with vast oil and gas reserves, brutal winters and a strong sense of economic self-interest.”[4] The New York Times wrote, “If the other leaders’ jaws did not drop, it was only because they were being polite. The remarks were a departure from Mr. Putin’s years of publicly mocking the issue. In 2003, for example, he noted that climate change could have the advantage of causing Russians to spend less on fur coats… Were Mr. Putin’s statements merely further attempts to win a place back in the international fold, after he was marginalized because of Russia’s aggression in Crimea, eastern Ukraine and Syria? Or were his remarks a sincere attempt to be a team player as almost 200 countries try to reach a climate deal?”[5] This author does not doubt that any of these reasons are false and that they did not influence Putin’s decision to appear cooperative. But is it possible that climate change is a real threat to Russia’s interests?

Some climate change skeptics in Russia believe that the effects of climate change will benefit Russia (melting permafrost would open the Arctic regions for oil and gas production and the Northern Sea Route for trade, more agricultural opportunities with warming temperatures in previously non-arable land, etc.). Regarding the possibility of fuel production in the Arctic, technology has broken these barriers and recent news of the world’s biggest icebreaker suggests Russia will find a way.[6] And, of course, there is the Yamal project.[7] The Northern Sea Route does not seem to be a compelling enough reason either, as low oil prices have diminished the investment attractiveness of this shipping route.[8] As for the prospects of increased grain production possibilities, it’s difficult to address such a ridiculous notion.

Whether Putin’s comment was a joke and the humor was lost on Western journalists or whether Putin has simply changed his tone, today’s Russia acknowledges that global warming conflicts with Russia’s interests. Eroding shorelines, the impact on permafrost areas (which account for 60 percent of its territory), increased duration of wildfires in Siberia, and desertification of the Caspian are only a handful of the many ways climate change can rear its ugly head in Russia.[9][10]

According to the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, average temperatures in Russia are warming 2.5 times faster than the Earth’s average.[11] The Minister of Natural Resources and Environment, Sergei Donskoy, stated, “extreme weather could cut Russia’s economic output by 1-2 percent every year for the next 15 years.”[12] Just last year, the wildfires that blazed across Siberia covered the lake “Pearl of Siberia” in ash. Furthermore, Former president Dmitry Medvedev initiated the law punishing companies who did not utilize 95 percent of their associated petroleum gas, significant given the country’s history of gas flaring.[13]

- Current Russian initiatives and the potential for growth in the renewable energy sector

Russia already possesses a highly skilled work force to develop its renewable energy sector. In the 1930s, the USSR was the first country to begin constructing utility-scale wind turbines.[14] And developing the renewable energy sector comes with massive benefits for the population. Roughly 16 million families own countryside homes (called dachas), where there is great potential for renewable-energy demand.

Russia’s vast territory allows for ample opportunities to harness energy produced by the sun and wind. Solar energy could be harnessed in the southwestern regions, including the North Caucasus, Black and Caspian Sea regions, Southern Siberia, and the Far East. The average radiation level is 1400 kWh/m2 per year. Wind energy could be developed in the coastal areas, particularly in the Far East and Black Sea regions.[15] Therefore, the potential is there. But is the intention? In 2009, Russia’s energy plan included a goal of increasing the percent of energy from renewables to 4.5 percent by 2020.[16] In an article written by Medvedev in 2009, he illustrates his desire to move away from the “habit of relying on the export of raw materials.”[17]

The barrier to these projects is therefore not lack of will, but the requirement of significant capital and technology, which Russia is currently having difficulty in accessing. Western sanctions initiated after the Crimea incident blocked access to Western financial markets and this has had the unintended effect of limiting Russia’s ability to go green. Renewable energy projects require much capital expenditure. I spoke with Maxim Titov, of the World Bank, who remarked how energy efficiency financing projects, which were gaining momentum before the sanctions, are indefinitely stalled.

There is hope, however. Current initiatives include work by RUSNANO, which Putin mentioned in his COP21 speech, which has produced a nanotube technology with the ability to reduce waste when applied to the manufacturing of certain materials.[18] Another company, Renova, has collaborated with the solar technology manufacturer, Hevel, which already runs three solar farms and recently opened a solar panel manufacturing plant. The company aims to invest 450 million USD in solar technology in the next three years.[19] Nevertheless, little growth is expected until the sanctions are lifted, as access to Western financial markets and technology is crucial to its development.

- Conclusion

The intention of this paper is not to persuade Western media outlets to be less hypercritical toward Russia, as it is obviously a futile effort. Rather, this author urges policymakers not to align themselves with those who see international affairs through the lens of us vs. them. Climate change action is already the quintessential collective action problem and all parties must be willing to set aside contentious issues and work together, especially when parties are willing. Moreover, the West must reevaluate its approach to characterizing Russia. For all the accusations from the West that the Russian media is corrupt and unreliable, perhaps Western journalists should be careful not to criticize Russia for the sake of criticizing Russia. Many Russians already believe that Western media is disproportionately critical of Russia. Bashing Putin for his climate change concerns, genuine or not, is counterproductive to the greater good. The motivations are certainly geopolitical. This explains why Saudi Arabia, the controversial and notably oil-rich U.S. ally, wasn’t subjected to the same criticism, despite actively trying to block an agreement, taking issue with the more ambitious 1.5-degree Celsius goal while, it being one of the richest countries in the world, refusing to financially assist countries in weaker economic positions.[20] Indeed, Russia’s emissions commitments are less than ambitious, but they are certainly significant.

Speaking at the opening of the Saint Petersburg International Economic Forum, which took place June 16-18, as this author penned this conclusion, U.N. Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon stressed the need for countries to adopt the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, while also thanking Russia for signing the crucial document. The West should take a cue from UNSG Ban-Ki Moon and welcome Russia’s commitment to climate change, because global warming doesn’t care about geopolitics and achieving progress will require all hands on deck.

Michael Roh

Michael Roh is an MA candidate in the ENERPO program at the European University at Saint Petersburg and served as Assistant Editor of the ENERPO Journal. Michael has a BA in Political Science from the City University of New York, Hunter College.

He can be reached at: mroh@eu.spb.ru

[1] Fern, 2016. What are carbon sinks? [online] Available at: http://www.fern.org/campaign/carbon-trading/what-are-carbon-sinks

[2] Poberezhskaya, M., 2015. Paris climate talks: Russia will use its huge forests as a bargaining chip at COP21. International Business Times, [online] 20 November. Available at: http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/paris-climate-talks-russia-will-use-its-huge-forests-bargaining-chip-cop21-1529685

[3] Climate Action Tracker, 2016. Russian Federation. [online] Available at: http://climateactiontracker.org/countries/russianfederation.html

[4] Poberezhskaya, M., 2015. Paris climate talks: Russia will use its huge forests as a bargaining chip at COP21. International Business Times, [online] 20 November. Available at: http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/paris-climate-talks-russia-will-use-its-huge-forests-bargaining-chip-cop21-1529685

[5] Davenport, C., 2015. A Change in Tone for Vladimir Putin’s Climate Change Pledges. The New York Times, [online] 1 December. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/projects/cp/climate/2015-paris-climate-talks/vladimir-putin-climate-change-pledges-russia

[6] Lockhart, K., 2016. Russia floats out ‘world’s biggest’ nuclear-powered icebreaker. The Telegraph, [online] 17 June. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/06/17/russia-floats-out-worlds-biggest-nuclear-powered-icebreaker/

[7] Novatek, 2016. Yamal LNG. [online] Available at: http://www.novatek.ru/en/business/yamal-lng/

[8] TASS, 2016. Investment attractiveness of Northern Sea Route falls with dwindling oil price. TASS, [online] 20 May. Available at: http://tass.ru/en/economy/877090

[9] Clark, W., & Elkin, D., 2015. Russia joins other nations in a historic climate change agreement. Russia Direct, [online] 14 December, Available at: http://www.russia-direct.org/opinion/russia-joins-other-nations-historic-climate-change-agreement

[10] Katona, V., 2016. Realizing Russia’s renewable energy potential in 2017. Russia Direct, [online] 1 February. Available at: http://www.russia-direct.org/opinion/realizing-russias-renewable-energy-potential-2017

[11] TASS, 2016. Russia signs Paris Agreement on Climate Change. TASS, [online] 22 April. Available at: http://tass.ru/en/politics/871982

[12] Kuzmin, A., 2015. Russian media take climate cue from skeptical Putin. Reuters, [online] 29 October. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-climatechange-summit-russia-media-idUSKCN0SN1GI20151029

[13] The World Bank, 2013. Igniting Solutions to Gas Flaring. [online] Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2013/11/12/igniting-solutions-to-gas-flaring-in-russia

[14] Clark, W., 2015. Russian Resources Start to Flow into Renewable Energy. The World Post, [online]. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/woodrow-clark/russian-resources-start-t_b_8215902.html

[15] Katona, V., 2016. Realizing Russia’s renewable energy potential in 2017. Russia Direct, [online] 1 February. Available at: http://www.russia-direct.org/opinion/realizing-russias-renewable-energy-potential-2017

[16] Clark, W., 2015. Russian Resources Start to Flow into Renewable Energy. The World Post, [online]. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/woodrow-clark/russian-resources-start-t_b_8215902.html

[17] Medvedev, D., 2009. Dmitry Medvedev’s Article, Go Russia! President of Russia, [online] 10 September. Available at: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/5413

[18] Clark, W., 2015. Russian Resources Start to Flow into Renewable Energy. The World Post, [online]. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/woodrow-clark/russian-resources-start-t_b_8215902.html

[19] Clark, W., 2015. Russian Resources Start to Flow into Renewable Energy. The World Post, [online]. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/woodrow-clark/russian-resources-start-t_b_8215902.html

[20] Ayed, N., 2015. Climate talks contend with both villains, heroes as deadline looms. CSC News, [online] 8 December. Available at: http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/climate-talks-contend-with-both-villains-heroes-as-deadline-looms-1.3355327

[1] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

[2] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2016. Background on the UNFCCC: The international response to climate change. [online] Available at: http://unfccc.int/essential_background/items/6031.php

[3] World Resources Institute, 2016. Understanding the IPCC Reports. [online] Available at: http://www.wri.org/ipcc-infographics

[4] Greenhouse gas

[5] TASS, 2016. Russia signs Paris Agreement on Climate Change. TASS, [online] 22 April. Available at: http://tass.ru/en/politics/871982

[6] Intended Nationally Determined Contribution

[7] Climate Action Tracker, 2016. Russian Federation. [online] Available at: http://climateactiontracker.org/countries/russianfederation.html

[8] Pearce, F., 2004. Russia set to approve climate change plan. The New Scientist, [online] 30 September. Available at: https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn6467-russia-set-to-approve-climate-change-plan/