By Lina Nagell

Abstract

This paper addresses two main questions. The first asks what the benefits to China are in joining the ECT, the second whether the One Belt, One Road Initiative will accelerate the country’s accession to the treaty. The paper finds that the main benefits facing Chinese accession to the ECT are: (1) the increased protection of Chinese foreign investments, (2) the improvement of investor confidence in the Chinese energy market, and (3) the boost of Chinese influence in global energy governance. The main obstacles are (1) fear of international arbitration cases against the Chinese government and (2) the scarcity of political support and geographically asymmetrical protection coverage for China. The paper also concludes that OBOR could indeed be an incentive for increased focus towards Chinese accession to the ECT and that this can again be influenced positively by a falling oil price.

Key words: OBOR; ECT; foreign investment; China.

China is facing a vastly different economic reality than has been the case since the country’s opening-up policy of the 1980’s.[1] A consistently high growth rate, around 9%, is expected to decline. China is thus seeking to expand to new markets, one way being through the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative. The initiative includes, but is not limited to, a variety of energy projects, which are of particular interest for China as the world’s largest energy consumer. There is the need to protect Chinese investments in energy projects in the over 65 countries bordering OBOR. In this regard, the relationship between China and the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) has blossomed over the last few years and culminated in the signing of the International Energy Charter (IEC) last year. It is seen by many as a first step towards ECT accession.2 In this paper I address two important questions:

What are the main benefits and obstacles regarding Chinese membership to the Energy Charter Treaty, and could the One Belt, One Road Initiative from 2013 quicken a possible Chinese accession to the treaty?

First, I introduce OBOR, before I contextualize the renewed Chinese focus on a possible ECT membership in later years, as well as the evolution of the treaty. Next, I present the ECT and the core issues as they pertain to this paper. Lastly, I present the main benefits and obstacles facing a Chinese ECT membership, and further explore OBOR’s ability to accelerate Chinese accession to the ECT before presenting my conclusions.

- The One Belt, One Road Initiative

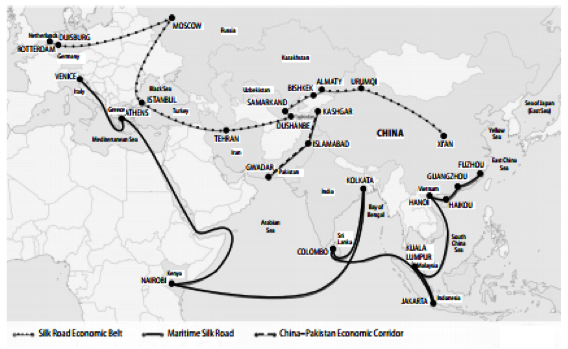

The One Belt, One Road (OBOR) [figure 1]3 initiative is one of China’s new tools to diversify trade routes and sustain growth rates.4 Through OBOR, the Chinese are hoping to expand trade volumes into new markets, especially in regards to industrial materials, of which China is currently experiencing a glut. At the same time, renewed investment into China, and the new trading routes, could help alleviate Chinese dependency on foreign oil traded through Pacific ports.4 There is also hope that the initiative could help translate China’s economic dominance into geopolitical power. The initiative was formally presented by President Xi Jinping as part of formal visits to the Central Asian states,5 but the idea has centuries` long roots in China. OBOR operates with two trading routes, one maritime, and one crossing Eurasia from China to Europe.6 Some of the major issues facing the successful implementation of OBOR are long-term cooperation with countries bordering the route, as well as the security of investments – in the energy sector in particular.5

China is not the first global actor to take the old traditional banner of the Silk Road, trying to modernize it, but they are the first actor to back it with considerable funding. OBOR includes a wide variety of energy projects and has indeed increased ambitions of energy contractors in the Chinese market.7 While contractors have focused more on China-friendly markets with lower competition in the past, growing confidence among actors, particularly in the energy sector, has actors looking towards the over 65 countries that border OBOR. There will be significant challenges for these investors when facing new economic and legal environments, and, on these issues, it is important to have a certain set of rules and a clear playing field between the investors and host-nations. It is in this regard that the ECT could play an important role in securing the implementation of OBOR. At the same time, increased popularity of OBOR could be thought to increase the potential of Chinese accession to the ECT.7 The drivers of Chinese focus towards OBOR, and the possibility of falling oil prices exacerbating this focus and its potential success, will be further discussed later in this paper.

- Renewed relevance of Chinese accession to the ECT and a changing global energy landscape

As the world’s largest energy consumer, and taking into consideration China’s new plans of increased investments in energy projects through OBOR, international energy cooperation is of special concern to the country. Pipelines and other energy infrastructure projects have gained positive momentum in recent years5 but risks regarding emergency response mechanisms, divergence in the allocation of new transit capacity along pipeline routes and investment protection in other countries, are still areas of concern. The current legal protections stipulated through existing Intergovernmental Agreements (IGA) and multilateral cooperative mechanisms, under the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), for example, are insufficient in ensuring the stability of energy flows for both existing and planned pipelines by a report published by the ECT in 2015, titled: Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China. Other issues concern Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs), in which some provisions are characterized as too conservative and less oriented towards investors.8 Indeed, of the approximately 65 countries bordering OBOR, so far 38 have signed BITs – but some of these are limited to determine the amount of compensation in case of expropriation, and are again seen as insufficient.9 In this context, a more comprehensive multilateral legal framework, such as one presented through the ECT, could benefit China.

One of the reasons China has not yet acceded to the ECT, may be based on the impression that multilateral energy organizations have been structured around the interests of powerful economies or energy-rich countries (specifically based in Europe since its infancy) – leaving smaller countries to prefer the development of relationships with major actors through bilateral cooperation.8 In this sense, there has not been a great need for China to accede to the ECT, as it was originally outside of the initial scope of the treaty, and smaller nations working together with China may not have seen its interests best served through the ECT, opting for BIT`s with energy giant China instead. The ECT`s geographic focus on Europe in its infancy now appears to be changing through the IEC. A new era dominated by globalization, increased competition and technological advances, may have changed the needs for multiple global actors. In facing these new challenges, multilateral energy diplomacy is stated as having become more policy-focused and practical.8 The changing landscape alongside an increased willingness from international organizations to grow their member base, again exemplified by the ECT’s renewed efforts through the IEC,10 is leading smaller potential member states to believe that certain adjustments to better incorporate newcomers.

- The Energy Charter Treaty

The ECT was signed in 1994, entering into force in 1998.11 It builds on the 1991 Energy Charter (EC) – also known as the European Energy Charter.12 The EC is an expression of the foundations which should underlie international energy cooperation. Developed in the period following the Cold War, the EC and ECT exist to establish commonly accepted foundations for energy cooperation amongst states.12 China gained observer status to the ECT in 2001 and signed the International Energy Charter (IEC) in 2015. The IEC differs from the ECT in that it is a declaration of political intention, aiming at strengthening energy cooperation between the signatory states. While the ECT is legally binding, the IEC is not. The IEC may be considered a mechanism for expanding the ECT internationally, whereas the main goal of the ECT is to strengthen the rule of law on energy issues.13

Provisions within the ECT regarding foreign investments are considered a cornerstone of the treaty. The goal is to create a level playing field for investments made in the energy sector. Investments in the energy sector have a tendency to span long time periods and demand large investments. In this regard, it can take time before investors see a return on their investment. When an investment in a host-nation is made, the risk of obsolescing bargaining can also run deep. Obsolescing bargaining14 is the issue of risk allocating rapidly from the capital-hungry host state to the investor, once the initial investment (in energy projects often being the bulk of the investment) is made.13 Uncertainties in this regard lead to lack of confidence in the host nation’s market and deter future investments. It is important to note that the ECT does not create investment opportunities, but provides stable interface between the investor and the host-nation.15

One potential issue for new members to the ECT is the level of change thrust upon potential new members when acceding to the treaty. It is true that the ECT does not seek to determine the structure of national energy markets, dictate national energy policies or oblige member states to open up their energy sector to foreign investors,16 but at the same time member states are liable for suits posed by foreign investors in the energy market,17 This is something that could prove to be a difficult pill for the Chinese government to swallow. In this regard, a well-known part of the ECT, especially important when discussing a possible Chinese membership, is the investor-contracting party dispute mechanism (Article 26). Under this article it is stated that a contracting party: “shall give unconditional consent to the submission of a dispute from an investor of another contracting party to international arbitration.”15

Challenges facing the ECT, and which could potentially be the reason behind its renewed international focus, is the fragmentation of global energy governance, and a few hits that the ECT has taken over the years. With an original geographic background in Europe, the ECT has traditionally enjoyed backing from the EU. However, this has changed along with the establishment of other external policy instruments, such as the European Community Treaty. The decision of Russia to withdraw from the treaty in 2009 also had a damaging effect on the role played by the ECT in global energy governance.15 The advantage of the ECT is that it covers the entire value chain of the energy industry with multilaterally and legally binding obligations.17

- Benefits of Chinese accession to the ECT

4.1 Increased Protection of Chinese Foreign Investments

The renewed Chinese focus and investment made in energy infrastructure abroad is an important factor. These renewed efforts have left some of the host nations to question Chinese motives,18 one Chinese fear being that Chinese investments in strategically important industries could lead to political interference from host nations. In this regard, accession to the ECT is mentioned as a way to protect foreign Chinese investments. Other fears are investments being blocked by unfair or discriminative practices under an argument of matters of national security, as well as other political and economic considerations from the host countries. Here, as mentioned previously, the shortcomings of existing BITs are of particular concern.18 Indeed, BITs with several Central Asian countries are not legally binding, but all of these countries are signatories to the ECT.19

4.2 Improvement of Investor’s Confidence in the Chinese Energy Market

Within China, the ECT could also have a beneficial role to play. The dominant part played by State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) in the Chinese energy industry, alongside a scarcity of sufficient legal protection for foreign investments to China, is a concern and could dampen foreign investments to the Chinese energy market. In this regard, accession to the ECT could help improve China’s reputation as an investment destination. In light of increasing energy demand, the Chinese energy market is continuously being opened up to foreign investments in order to modernize and introduce new technology.18 There are many obligations and responsibilities for potential members stipulated in the ECT and, in this regard, Chinese accession to the ECT would promote the optimization of the domestic legal environment and help increase investor confidence.18

As mentioned, the ECT may leave the member state in question quite free to determine the system of property ownership of its national energy resource, while at the same time opening it up for suits from new investors.20 In this regard, there is a good chance that the Chinese government will think twice before acceding to the ECT. Taking into consideration that a relatively new government, led by President Xi Jinping, is believed to further consolidate its power at the National Congress of the Communist Party set for 2017,21 this might not be the time for opening up the Chinese economy further – politically. At the same time, the sitting government is increasingly concerned about diminishing growth rates, something that could be alleviated somewhat with increased investments resulting from accession to the ECT. Indeed, it is suggested by Wang that, “with Chinese accession to the ECT, it is reasonable to believe that more foreign energy investment with outstanding expertise will flow into the Chinese domestic energy industry and, more importantly, will make a certain contribution to the sustainable development of the Chinese economy and society in the long run.”22

4.3 Boost of Chinese influence in global energy governance

As the global energy landscape is being transformed due in part to increasing demand from BRICS countries and increased efforts to reduce carbon emissions from, amongst others, developing nations as well as developed nations, it is argued by Wang that China will play an increasing role in global energy dominance, as the largest developing country in the world.22 The ECT offers one way for China to fulfill its deeper involvement in global energy governance. China would, if acceding to the ECT, be in a position where it could communicate and cooperate22 with all member states of the ECT, an advantage when seeking a leading role. China would also be able to influence the framework of the ECT to a greater extent as a full-fledged member.

- Obstacles facing Chinese accession to the ECT.

5.1 Fear of international arbitration cases against the Chinese government

There is still a great deal of support within the Chinese government to characterize the energy industry as important to national security and social stability, as is to be expected. This idea stands in the way of the promotion of reform and liberalization of the economy.23 The road to a fully competitive energy market in China is partly blocked by this fear. Bearing in mind Article 26 of the ECT, a major concern is that utilization of this clause will impose potential arbitration burdens on the Chinese government. Libin Zhang states that the benefits of a Chinese accession to the ECT outweighs the costs, but it is important to note that the Chinese government’s main objective may not be purely economic – it also needs to continue its hold on power, something which could be challenged through these suits.24 It is also noted by Wang that lack of experience and knowledge surrounding international arbitration procedures within the ECT is something that must be rectified before any Chinese accession to the ECT.24

5.2 Scarcity of political support and geographically asymmetrical protection coverage for China

The ECT’s role in global energy governance has changed since its initiation, something that might be one of the contributing factors to its renewed international focus. Despite the aforementioned advantages of the ECT, there is a concern that the focus on legal aspects of the energy value chain might be too wide to be addressed by the ECT,23 the fear being that too wide a focus will lead to a decline in political attachment to the ECT. Geographically asymmetrical protection coverage, Chinese cooperation with certain countries not party to the ECT contra Chinese cooperation with countries which are members of the ECT, are by some seen as an obstacle. Other observers, however, note that the international scope of the IEC and ECT might see these issues resolve themselves in the near future.23

- OBOR – An incentive for Chinese ECT accession?

OBOR could work as an incentive for Chinese accession to the ECT. An interesting point however, is that OBOR has tended to fluctuate in importance for the Chinese government, at times being little more than a loose set of ideas not being comprehensibly implemented. The fall of the oil price does have the potential to increase the importance and probability of OBOR being successfully implemented and possibly refocus China towards the ECT.25 As many of the countries along the OBOR route are highly dependent on the trading of natural resources, these countries could struggle under falling oil prices and might be more inclined to accept Chinese investment pitches, as well as to taking a share in China’s $40 billion (US) Silk Road Infrastructure Fund. This situation could increase willingness from both the Chinese government and potential trading partners to focus on OBOR and subsequently incentivize Chinese accession to the ECT.25

- Conclusions

What are the main benefits and obstacles regarding Chinese membership to the Energy Charter Treaty, and could the One Belt, One Road Initiative from 2013 accelerate a possible Chinese accession to the treaty?

It is my conclusion that the main benefits facing Chinese accession to the ECT are:

- Increased protection of Chinese foreign investments

- Improvement of investor confidence in the Chinese energy market

- A boost of Chinese influence in global energy governance

The main obstacles are:

- Fear of international arbitration cases against the Chinese government

- The scarcity of political support and geographically asymmetrical protection coverage for China

I also conclude that OBOR could indeed be an incentive for increased focus towards Chinese accession to the ECT and that this can again be influenced positively by a falling oil price.

Lina Nagell

Lina Nagell is an MA candidate in the ENERPO program at the European University at Saint Petersburg. Lina holds two BA degrees, one in Comparative Politics and one in Economics, both from the University of Bergen (Norway).

She can be reached at: linanagell@gmail.com

1 Wang, Zhuwei, 2015. Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China. Energy Charter Secretariat. [online] Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-20/commodities-meltdown-boosts-china-s-bid-to-build-new-silk-road

2 Zhang, Libin, 2016. China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the Energy Charter Treaty. International Law Office (ILO). [online] Available at: http://www.internationallawoffice.com/Newsletters/Energy-Natural-Resources/China/Broad-Bright/Chinas-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-and-the-Energy-Charter-Treaty?redir=1

3 Nataraj, Geethanjali & Richa Sekhani, 2015. China`s One Belt One Road, An Indian Perspective. Economic & Political Weekly, Vol L, No. 49. [online] Available at: http://dev.epw.in/system/files/pdf/2015_50/49/Chinas_One_Belt_One_Road.pdf

4 Pavlicevic, Dragan, 2015. China, the EU and One Belt, One Road Strategy. The Jamestown Foundation. [online] Available at: http://www.jamestown.org/programs/chinabrief/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=44235&cHash=9dbc08472c19ecd691307c4c1905eb0c#.V2sh1pMrLEa

5 Wang, Zhuwei, 2015. Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China. Energy Charter Secretariat. [online] Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-20/commodities-meltdown-boosts-china-s-bid-to-build-new-silk-road

6 Pavlicevic, Dragan, 2015. China, the EU and One Belt, One Road Strategy. The Jamestown Foundation. [online] Available at: http://www.jamestown.org/programs/chinabrief/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=44235&cHash=9dbc08472c19ecd691307c4c1905eb0c#.V2siBJMrLEa

7 Jones, Greg, 2016. China’s ‘one belt, one road’ policy increasing the ambitions of its energy contractors. Out-law.com. [online] Available at: http://www.out-law.com/en/articles/2016/january/chinas-one-belt-one-road-policy-increasing-the-ambitions-of-its-energy-contractors/

8 Wang, Zhuwei, 2015. Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China. Energy Charter Secretariat. [online] Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-20/commodities-meltdown-boosts-china-s-bid-to-build-new-silk-road

9 Zhang, Libin, 2016. China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the Energy Charter Treaty. International Law Office (ILO). [online] Available at: http://www.internationallawoffice.com/Newsletters/Energy-Natural-Resources/China/Broad-Bright/Chinas-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-and-the-Energy-Charter-Treaty?redir=1

10 Zhang, Libin, 2016. China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the Energy Charter Treaty. International Law Office (ILO). [online] Available at: http://www.internationallawoffice.com/Newsletters/Energy-Natural-Resources/China/Broad-Bright/Chinas-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-and-the-Energy-Charter-Treaty?redir=1

11 Selivanova, Yulia, 2012. The Energy Charter and the International Energy Governance. European Yearbook of International Economic Law (EYIEL), Vol. 3.

12 Energy Charter Treaty, 2016. Investment. [online] Available at: http://www.energycharter.org/what-we-do/investment/overview/

13 Wang, Zhuwei, 2015. Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China. Energy Charter Secretariat. [online] Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-20/commodities-meltdown-boosts-china-s-bid-to-build-new-silk-road

14 Martin, Timothy A. Dispute Resolution in the International Energy Sector: an overview. Journal of World Energy Law and Business, 2011, Vol. 4, No. 4.

15 Wang, Zhuwei, 2015. Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China. Energy Charter Secretariat. [online] Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-20/commodities-meltdown-boosts-china-s-bid-to-build-new-silk-road

16 Energy Charter Treaty, 2016. Investment. [online] Available at: http://www.energycharter.org/what-we-do/investment/overview/

17 Zhang, Libin, 2016. China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the Energy Charter Treaty. International Law Office (ILO). [online] Available at: http://www.internationallawoffice.com/Newsletters/Energy-Natural-Resources/China/Broad-Bright/Chinas-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-and-the-Energy-Charter-Treaty?redir=1

18 Wang, Zhuwei, 2015. Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China. Energy Charter Secretariat. [online] Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-20/commodities-meltdown-boosts-china-s-bid-to-build-new-silk-road

19 Zhang, Libin, 2016. China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the Energy Charter Treaty. International Law Office (ILO). Available at: http://www.internationallawoffice.com/Newsletters/Energy-Natural-Resources/China/Broad-Bright/Chinas-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-and-the-Energy-Charter-Treaty?redir=1

20 Energy Charter Treaty, 2016. Investment. [online] Available at: http://www.energycharter.org/what-we-do/investment/overview/

21 The Manila Times, 2016. Stratfor analysis, China: Raising the stakes in Xi’s consolidation of power. The Manila Times. [online] Available at: http://www.manilatimes.net/china-raising-the-stakes-in-xis-consolidation-of-power/246774/

22 Wang, Zhuwei, 2015. Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China. Energy Charter Secretariat. [online] Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-20/commodities-meltdown-boosts-china-s-bid-to-build-new-silk-road

23 Wang, Zhuwei, 2015. Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China. Energy Charter Secretariat. [online] Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-20/commodities-meltdown-boosts-china-s-bid-to-build-new-silk-road

24 Zhang, Libin, 2016. China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the Energy Charter Treaty. International Law Office (ILO). [online] Available at: http://www.internationallawoffice.com/Newsletters/Energy-Natural-Resources/China/Broad-Bright/Chinas-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-and-the-Energy-Charter-Treaty?redir=1

25 Shi, Ting, 2016. Commodities Crash Boosts China’s New Silk Road. Bloomberg Business. [online] Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-20/commodities-meltdown-boosts-china-s-bid-to-build-new-silk-road